For a while earlier this summer, it looked like NASA’s flagship mission to study Jupiter’s icy moon Europa might miss its launch window this year.

In May, engineers raised concerns that transistors installed throughout the spacecraft might be susceptible to damage from radiation, an omnipresent threat for any probe whipping its way around Jupiter. The transistors are embedded in the spacecraft’s circuitry and are responsible for approximately 200 unique applications, many of which are critical to keeping the mission operating as it orbits Jupiter and repeatedly zooms by Europa, interrogating the frozen moon with nine science instruments.

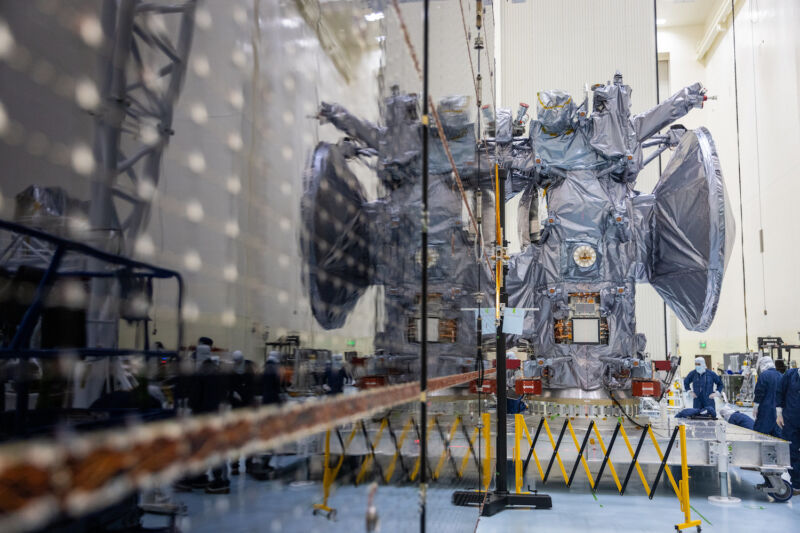

The transistors on the Europa Clipper spacecraft are already installed, and removing them for inspections or replacement would delay the mission’s launch until late next year. Europa Clipper has a 21-day launch window beginning October 10 to begin its journey into the outer solar system.

After four months of testing similar transistors on the ground, engineers determined the transistors on Europa Clipper could withstand the extreme radiation the spacecraft would encounter around Jupiter, without any changes to the mission’s flight plan or trajectory.

“One big challenge was analyzing how those transistors on the spacecraft would handle the radiation environment at Jupiter,” said Jordan Evans, Europa Clipper’s project manager at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). “After extensive testing and analysis of the transistors, the Europa Clipper project and I, personally, have high confidence we can complete the original mission for exploring Europa as planned.”

Senior NASA officials decided Monday that they agreed with the assessment of Europa Clipper’s team at JPL.

“It is wonderful to be here with incredibly good news,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator of NASA’s science mission directorate. “We’re all extremely happy here. Extremely hot off the press, we did just put the Europa Clipper mission through a key milestone review … the last big review before we really get into that launch fever, and we’re really happy to say that they unequivocally passed that review today.”

With approval from NASA headquarters, teams preparing Europa Clipper for launch at Kennedy Space Center in Florida will begin loading approximately 3 metric tons (6,600 pounds) of propellant into the spacecraft later this week. That’s roughly half of the total weight of the Europa Clipper spacecraft, the largest probe NASA has ever built for planetary exploration. Then, NASA and SpaceX technicians will enclose the probe inside its launcher fairing and connect it with a Falcon Heavy rocket for liftoff next month.

“I am thrilled to say that we are confident that our beautiful spacecraft and capable team are ready for launch, operations, and our full science mission at Europa,” said Laurie Leshin, center director at JPL.

This is a rad mission

After setting off from Florida’s Space Coast next month, Europa Clipper will reach Mars in February 2025 for a gravity assist flyby to gain speed on the journey to Jupiter. A subsequent flyby with Earth in December 2026 will bend the path of Europa Clipper to intercept Jupiter’s orbit in April 2030, when the probe will fire its engine to slow down for capture by the giant planet’s immense gravity field.

Then, Europa Clipper will set itself up on a trajectory to fly by Europa 49 times over about four years, coming as close as 16 miles (25 kilometers) from the moon’s icy surface. The instruments aboard Europa Clipper will map most of the moon’s icy crust and search for signs that Europa’s subsurface ocean of liquid water might be habitable for life. If scientists are lucky, the spacecraft could also fly through plumes erupting from Europa’s surface, and these eruptions might contain pristine materials from the ocean under its icy shell. If that happens, Europa Clipper’s instruments will get a taste of the chemistry of Europa’s ocean.

“This is an epic mission,” said Curt Niebur, Europa Clipper’s program scientist at NASA Headquaters. “It’s a chance for us to explore not a world that might have been habitable billions of years ago, but a world that might be habitable today, right now.”

Europa, about 90 percent the size of Earth’s Moon, circles Jupiter in the outer edge of the planet’s radiation belts, where charged particles can zap the electronics of any spacecraft that dares to transit the region.

The most sensitive electronics on Europa Clipper are mounted inside a vault with walls of aluminum-zinc alloy to shield the components from Jupiter’s radiation. Many of the transistors on the spacecraft are located within this vault, but others are built into science instruments located on the outer edges of the spacecraft.

The transistors have a self-healing property known as annealing, allowing them to recover much of their capacity after exposure to intense radiation. For most of Europa Clipper’s orbit around Jupiter, the spacecraft flies in a more benign radiation environment, allowing time for the transistors to repair themselves between close flybys of Europa, where the radiation is worst. The only change mission managers will make on Europa Clipper will be to adjust heater settings around some of the suspect transistors on two instruments outside of the vault. Warmer temperatures allow the components to self-heal more efficiently.

“These are metal oxide field effect transistors, so think of them as electronic switches where you apply a voltage, and you can close an electronic switch,” Evans said.

“In some cases, the switch just basically goes on permanently, and if that switch was turning on a little 1-watt decontamination heater, well then that’s really not a big deal to the mission,” Evans said. “But if that circuit is telling the spacecraft that it needs to go into safe mode, that’s a little bigger deal. It’s a much bigger deal. So we analyzed every one of those circuits and how robust and tolerant they are to degraded transistors, and determined that we had sufficient margin in every one of those circuits to accomplish this flagship mission with confidence.”